Foundations of Algorithmic Randomness and Computability

Written jointly with Elan Roth

Introduction

This post explores two fundamental questions: what does it mean to be random, and what does it mean to compute? We develop the theory of computation and algorithmic randomness by introducing historical background, the central constructions in computability theory, and three mathematical approaches to defining randomness. Our discussion is enriched by a formalization written in the Lean theorem prover, and code snippets will be used throughout the text to supplement and substantiate the ideas we present.

I. History

The Dream of Mechanical Reasoning

At the turn of the twentieth century, David Hilbert expressed the belief that all of mathematics could be reduced to mechanical symbolic manipulation, void of the need for human insight or creativity. If we could just find the right formal system, the right rules for pushing symbols around, then we could put any conjecture into a machine and receive either a proof or a refutation. In terms that hadn’t yet been coined, he believed in the existence of an algorithm for deciding all mathematical truth. This was referred to as the Entscheidungsproblem.

To answer this question positively, one would simply have to provide such an algorithm. But to prove such a machine does not exist, we need to step back and answer a more fundamental question: what is an algorithm?. Before the 1930s, this notion lived only in intuition. Computation had the status of “I know it when I see it”. But to make progress on this question we had to put the notion on formal grounds.

In the 1930s, Turing, Church, and Gödel each provided rigorous definitions of computability, and these definitions gave us the tools to prove Hilbert wrong. Gödel’s incompleteness theorems showed that any sufficiently powerful formal system contains true statements it cannot prove, Turing proved that no algorithm can decide whether an arbitrary program halts, and the fully mechanical mathematician was proven impossible.

Still, something survives from Hilbert’s vision. We cannot mechanize the discovery of all mathematical truth, but we can mechanize its verification. Modern proof assistants like Lean, Coq, and Isabelle let us write proofs in formal languages where every step is checked against a set of rules encoded into the language. The computer cannot tell us what to prove or how, but it can confirm, with absolute certainty, that our reasoning is valid.

While Gödel and Turing’s results provide hard theoretical limits on computation, recent progress in machine learning suggests that some sufficiently advanced models may be able to approximate Hilbert’s dream in practice. Modern systems have very recently been able to generate formal proofs of previously unsolved problems, do graduate-level mathematics, and win the most difficult math competitions. They’re beginning to assist not just with verification but with actual mathematical discovery. One can imagine an AI system powerful enough to answer, with high probability, every mathematical question humans actually want to ask, and this would resemble Hilbert’s magical oracle.

Three Models of Computation

In the 1930s, three mathematicians working independently proposed formal definitions of computability. Alan Turing imagined an idealized human computer: someone with unlimited paper, a finite set of instructions, and infinite patience. Alonzo Church built a calculus of pure functions, where computation meant simplifying terms by applying and substituting. And Kurt Gödel, building on work by Herbrand, defined a class of arithmetic functions that could be built from simple pieces using specific construction rules.

Turing machines. Alan Turing’s idealized human computer: someone with unlimited paper tape divided into cells, and a finite set of instructions. The machine reads one cell at a time, writes a symbol, moves left or right, and transitions between states according to fixed rules. Turing claims a function is computable if there is a Turing machine which will halt and return the output of the function.

Lambda calculus. Alonzo Church’s calculus of pure functions. This is a language that consists of simple expressions that can be applied to other expressions and simplified by substituting variables. Church claims a function is computable if it can be written as a lambda expression.

Recursive functions. Kurt Gödel’s class of number-theoretic functions built from simple primitives: zero, successor, projections—using composition, primitive recursion, and unbounded search. Gödel claims a function is computable if it belongs to this class.

The Church-Turing Thesis

Surprisingly, it turns out that these seemingly different notions of computation - computation as instruction following, computation as term simplification, and computation as recursion on $\mathbb{N}$ - are exactly equivalent. This is a mathematical theorem: any Turing-computable function is lambda-definable, any lambda-definable function is recursive, and any recursive function is Turing-computable.

The Church-Turing thesis is a philosophical claim asserting that this shared class captures precisely the functions that are computable in the intuitive sense: that our formal definitions match what we mean when we speak of computation. Since “intuitive computability” is not a mathematical concept, this claim cannot be proven, and is a hypothesis about how our mathematical formalisms capture physical reality.

While the CT thesis can’t be proven, this convergence provides pretty convincing evidence of its truth. Three mathematicians with different motivations and different formalisms arrived at the same boundary. Every subsequent attempt to formalize computation—register machines, Post systems, cellular automata—has yielded the same class of functions. When every reasonable approach produces identical results, we have good reason to believe we’ve identified something fundamental about the universe.

II. Formal Introduction

Partial Recursive Functions

We work with the recursive function approach, as it connects most directly to our formalization. A partial recursive function is built from simple primitives using a small set of operations. The word “partial” matters here: these functions need not be defined everywhere. A computation might run forever without producing an answer.

The computable primitives:

Zero: The constant function returning 0, regardless of input.

Successor: Given $n$, return $n + 1$.

Projections: Given a tuple of inputs, extract one component. The left projection takes $(a, b)$ to $a$; the right projection takes $(a, b)$ to $b$.

From these atoms, we build molecules using three operations:

Pairing/Composition: If we can compute $f$ and $g$, we can compute their composition $f \circ g$, and we can compute functions that combine their outputs.

Primitive Recursion: This captures the idea of computing by induction. Given a base case function $f$ and a step function $h$, we define:

\[\begin{aligned} \text{rec}(a, 0) &= f(a) \\ \text{rec}(a, n+1) &= h(a, n, \text{rec}(a, n)) \end{aligned}\]The value at $n+1$ depends on the value at $n$. This is how you’d compute factorial, exponentiation, or any function defined by “do the previous thing, then one more step.”

Unbounded Search (μ-minimization): This is where partiality enters. Given a function $f(a, n)$, the μ-operator searches for the smallest $n$ such that $f(a, n) = 0$:

\[\mu n. [f(a, n) = 0] = \text{the least } n \text{ with } f(a, n) = 0\]If no such $n$ exists, the search runs forever. The function is undefined at that input.

μ-Minimization

Primitive recursion alone gives you a lot: all the arithmetic operations, primality testing, anything with a predictable runtime. But it doesn’t give you everything computable.

Consider the following problem: given a description of a computation, find when (if ever) it terminates. This requires searching through time steps 0, 1, 2, … until termination occurs. There’s no bound you can compute in advance. You must simply search, and the search may never end.

The μ-operator is what separates the primitive recursive functions from the partial recursive functions. It’s the source of undecidability, of partial functions, of computations that might diverge. It’s also what makes the recursive functions powerful enough to capture all of computation.

Oracles and Relative Computability

We can all recognize that some problems are harder than others. In computability we are interested in comparing the relative difficulty of computational problems. One way to compare difficulty is through reducibility. Reducibility is a way of converting one problem into another, something which naturally comes up in everyday life. For example, if you are looking to find your way to a certain destination, this becomes easy if you are able to obtain a map to your destination, i.e. the problem of finding your destination reduces to finding a map to it. Another way to look at it is: the problem of finding your destination is no more unsolvable than the problem of obtaining a map.

Suppose we augment our computing device with an oracle, a black box that instantly answers queries about some function $g$. We can’t see inside the box; we just submit inputs and receive outputs, at zero cost. A function $f$ is recursive in $g$ (written $f \leq_T g$ for Turing reducibility) if $f$ can be computed by a machine with oracle access to $g$. This relation captures a notion of relative difficulty: $f \leq_T g$ means “$f$ is no harder to compute than $g$,” or “if someone handed us the answers for $g$, we could compute $f$.”

The formal definition extends partial recursive functions by adding oracle calls as primitives:

inductive RecursiveIn (O : Set (ℕ →. ℕ)) : (ℕ →. ℕ) → Prop

| zero : RecursiveIn O fun _ => 0

| succ : RecursiveIn O Nat.succ

| left : RecursiveIn O fun n => (Nat.unpair n).1

| right : RecursiveIn O fun n => (Nat.unpair n).2

| oracle : ∀ g ∈ O, RecursiveIn O g

| pair ... | comp ... | prec ... | rfind ...

The oracle constructor says: any function in our oracle set $O$ is computable relative to $O$. Everything else is the same machinery of pairing, composition, primitive recursion, and search.

μ-Minimization is encoded as:

| rfind {f : ℕ →. ℕ} (hf : RecursiveIn O f) :

RecursiveIn O fun a =>

Nat.rfind fun n => (fun m => m = 0) <$> f (Nat.pair a n)

The Nat.rfind searches for the first $n$ where $f(a, n) = 0$. If found, it returns that $n$. If $f(a, n) \neq 0$ for all $n$, the result is Part.none: undefined.

Degrees of Unsolvability

The reducibility relation orders problems by their inherent complexity. It is reflexive: any problem reduces to itself, since you can just solve it directly. It is transitive: if $f$ reduces to $g$ and $g$ reduces to $h$, then $f$ reduces to $h$ by chaining the reductions. But it is not antisymmetric. Two genuinely different problems can be mutually reducible, each one solvable given access to the other. When this happens, we say $f$ and $g$ are Turing equivalent ($f \equiv_T g$). They sit at the same level of difficulty.

A Turing degree is an equivalence class of problems under this mutual reducibility. All problems in a degree share the same computational complexity in a fundamental sense: each can simulate any other. The degree itself represents a “level” of unsolvability, an abstract measure of how hard its member problems are.

abbrev TuringEquivalent (f g : ℕ →. ℕ) : Prop :=

AntisymmRel TuringReducible f g

abbrev TuringDegree :=

Antisymmetrization _ TuringReducible

To compare degrees rather than individual functions, we must lift the ordering. We say degree a is below degree b (written a $\leq$ b) if some representative of a reduces to some representative of b.

With this lifted ordering, the Turing degrees form a partial order: reflexive, transitive, and now antisymmetric by construction. Two degrees are equal exactly when their members are mutually reducible. At the bottom sits $\mathbf{0}$, the degree containing all computable functions. These are the “easy” problems, solvable by algorithms with no oracle at all. They’re all Turing-equivalent to each other: any computable function can compute any other without an oracle.

The Structure of the Degrees

The simplest non-computable degree is $\mathbf{0’}$ (read “zero jump”), the degree of the halting problem. Given an encoding of programs, the halting problem asks: does program $e$ halt on input $n$? Turing proved that no computable function can answer this question for all pairs $(e, n)$. Yet the halting problem is well-defined as a set, and any function that could answer it would live in degree $\mathbf{0’}$.

The relationship between 0 and 0’ is an instance of a general construction called the jump operator. Given any function $f$, its jump $f’$ is the relativized halting problem: which programs halt when given oracle access to $f$? We can simulate any $f$-oracle program step by step, so $f’$ is computable from $f$. But crucially, $f’$ is never computable in $f$. The same diagonalization that makes the halting problem undecidable relativizes: no $f$-oracle program can decide which $f$-oracle programs halt. This means the degrees are unbounded from above. For any degree a, the jump a’ sits strictly higher:

\[\mathbf{0} < \mathbf{0'} < \mathbf{0''} < \mathbf{0'''} < \cdots\]One might imagine that the hierarchy of degrees forms a linear chain, ie. that the degrees are totally ordered. However, in 1956, Friedberg and Muchnik independently proved that there exist incomparable degrees: degrees a and b such that neither a $\leq$ b nor b $\leq$ a. This shows that some problems are incommensurable in difficulty; neither helps you solve the other.

More specifically the degrees form a join semilattice: any two degrees a and b have a least upper bound a $\lor$ b. Picture the structure as branching upward everywhere. From $\mathbf{0}$, it fans out into continuum-many incomparable directions. There are minimal degrees just above $\mathbf{0}$ with nothing between. There are dense chains. There are antichains of any finite size. Any two degrees can be joined, so paths merge going up. But there’s no ceiling, and no uniform way to factor a degree into simpler pieces.

In Lean, we define the join by interleaving: even inputs query $f$, odd inputs query $g$, and we encode which oracle answered in the output.

def join (f g : ℕ →. ℕ) : ℕ →. ℕ :=

fun n =>

cond n.bodd

( (g n.div2).map (fun y => 2 * y + 1) )

( (f n.div2).map (fun y => 2 * y) )

infix :50 " ⊕ " => join

This definition of join forms the least upper bound (supremum) in our lattice:

lemma left_le_join (f g : ℕ →. ℕ) : f ≤ᵀ (f ⊕ g)

lemma right_le_join (f g : ℕ →. ℕ) : g ≤ᵀ (f ⊕ g)

lemma join_le (f g h : ℕ →. ℕ) (hf : f ≤ᵀ h) (hg : g ≤ᵀ h) : (f ⊕ g) ≤ᵀ h

Using some quotient machinery we can lift this to a least upper bound on degrees, which gives us the following instance:

instance instSemilatticeSup : SemilatticeSup TuringDegree where

sup := sup

le_sup_left := le_sup_left

le_sup_right := le_sup_right

sup_le _ _ _ := sup_le

One mysterious part of the structure of the Turing degrees is its automorphism group, $Aut(\mathbf{T})$. An automorphism of the Turing degrees is a permutation $\pi$ that preserves the ordering in both directions: $a \leq b$ if and only if $\pi(a) \leq \pi(b)$. The trivial automorphism is the identity function. There is an open conjecture which asks whether there are any non-trivial automorphisms at all. The closest we’ve gotten is from Slaman and Woodin, who proved that $Aut(\mathbf{T})$ is at most countable - we don’t know if there are more than one, but we know there are fewer than there are real numbers!

These different aspects of this structure matter for randomness. When we say a sequence is “random,” we are making a claim about its computational properties. Random sequences are incomputable—they sit strictly above $\mathbf{0}$—and they resist computation in specific, measure-theoretic ways.

Gödel Encoding: Programs as Numbers

A key technique running through all of computability theory is Gödel encoding, the representation of syntactic objects as natural numbers. Programs, formulas, proofs, and even other encodings can all be assigned numerical codes.

The basic intuition is straightforward. A program is a finite string of symbols. We can list all such strings and assign each a unique natural number. Given the number, we can recover the string; given the string, we can compute its number. In our formalization, we encode the syntax of oracle computations:

def encode : Program → ℕ

| .zero => 0

| .succ => 1

| .left => 2

| .right => 3

| .oracle i => 4 + 5 * i

| .pair p q => 4 + (5 * Nat.pair (encode p) (encode q) + 1)

| .comp p q => 4 + (5 * Nat.pair (encode p) (encode q) + 2)

| .prec p q => 4 + (5 * Nat.pair (encode p) (encode q) + 3)

| .rfind p => 4 + (5 * encode p + 4)

Each constructor of our Program type maps to a distinct numerical range. The pairing function Nat.pair lets us encode composite structures into single numbers, and the coefficients (the factors of 5 plus offsets) ensure we can always decode unambiguously.

Decoding reverses this: we inspect the residue mod 5 to determine the constructor, then recurse on the quotient.

def decode : ℕ → Program

| 0 => .zero

| 1 => .succ

| 2 => .left

| 3 => .right

| n + 4 =>

let q := n / 5

match n % 5 with

| 0 => .oracle q

| 1 => .pair (decode q.unpair.1) (decode q.unpair.2)

| 2 => .comp (decode q.unpair.1) (decode q.unpair.2)

| 3 => .prec (decode q.unpair.1) (decode q.unpair.2)

| _ => .rfind (decode q)

These are inverses:

theorem decode_encode (c : Program) : decode (encode c) = c

As programmers we all know that programs can call other programs. Encoding allows this intuitive idea to be made formal. If programs are numbers, then a program can take another program’s code as input and simulate it step by step. A universal machine does exactly this: given a code $e$ and input $n$, it runs whatever program $e$ specifies on $n$.

Gödel encoding also enables self-reference. A program can receive its own code as input. This is how Gödel constructed his incompleteness sentences, and it underlies many undecidability proofs. In our setting, it lets us state and prove that the evaluation function eval is universal: every function recursive in an oracle has some code that eval will faithfully execute.

theorem exists_code {α : Type} [Primcodable α] (g : α → ℕ →. ℕ) (f : ℕ →. ℕ) :

RecursiveIn (Set.range g) f ↔ ∃ p : Program, eval g p = f

This theorem is the formal statement of universality. A function is recursive in $g$ if and only if it has a code. The encoding bridges syntax and semantics: it lets us treat programs as data, feeding a program its own code as input.

This encoding additionally allows us to define the jump operator mentioned previously.

def jump (f : ℕ →. ℕ) : ℕ →. ℕ :=

λ n => eval (λ _ : Unit => f) (decode n) n

To compute the jump of an oracle $f$ on input $n$, we decode $n$ as a program, run that program on input $n$ with oracle access to $f$, and return whatever it returns. The domain of this function—the set of $n$ where the $n$-th $f$-oracle program halts on itself—is the halting problem relative to $f$.

The theory developed in this section allows us to study infinite objects through the lens of computation. In particular, we can ask whether an infinite binary sequence can be predicted, compressed, or successfully exploited by any algorithmic procedure. This viewpoint leads to computability-theoretic definitions of randomness, which introduce in the next section.

III. Three Definitions of Randomness

Armed with this hefty tool we call “computation,” we may use against another abstract notion: Randomness. What is randomness? Intuitively we may have some ideas, but formalization requires rigor. First, we must fix an object of study. What things are we going to classify as random or not random? As algorithmic randomness is a field within theoretical computer science, those who came before us chose infinite binary sequences. Here are a few examples:

- $A_1 := 000 \dots$

- $A_2 := 01010101 \dots$

- $A_3 := 10110111011110111110 \dots$

- $A_4 := 10100101001011101001 \dots$

Which ones do you think are random? What pattern do the non-random seeming ones follow? You may have noticed that the use of $\dots$ is leading; stopping after three $0$’s in $A_1$ clearly indicates that the $0$’s will repeat, and similarly with the pattern $01$ in $A_2$. So these are definitely not random. $A_3$ and $A_4$ are left for your consideration. We urge you to pause and attempt to define your own notion of randomness. We present below three individuals’ characterizations of random binary sequences. Is yours similar?

Kolmogorov Complexity and Incompressibility

To study the first notion, we must humble ourselves. Infinite binary strings are impossible to fathom because (and only because) they are infinite. While we cannot grasp infinity, we can appeal to the finite world we do understand. Where we can put our conveniently formalized theory of computation into action. With these tools, we can reasonably observe arbitrarily long initial segments of our infinite binary string in question.

Using the same idea of encoding programs as above, we can encode finite binary strings into natural numbers in order to use the recursive functions. Note that decode_encode asserts that we can go back and forth between binary strings and natural numbers without losing any data.

abbrev BinSeq := List Bool

def encode : BinSeq → Nat

| [] => 0

| b :: σ => 2 * encode σ + (if b then 2 else 1)

def decode : Nat → Option BinSeq

| 0 => some []

| n + 1 =>

if (n + 1) % 2 = 1 then List.cons false <$> (decode ((n + 1) / 2))

else List.cons true <$> (decode ((n + 1) / 2 - 1))

theorem decode_encode (σ : BinSeq) :

decode (encode σ) = σ

Algorithmic randomness uses the term “machine” to describe the lifting of a partially recursive function to take and return finite binary strings. Given some fixed machine, $M$, we can ask which strings it will output and how difficult it is to actually return them. For some finite binary string, $\sigma$, we may ask what is the shortest string such that running $M$ on that string will output $\sigma$. Formally, we can define Kolmogorov complexity with respect to a machine $M$ as

\[C_M(\sigma) = \min \lbrace \lvert\tau\rvert : M(\tau) = \sigma \rbrace\]where $\lvert\tau\rvert$ denotes the length of $\tau$ and $M(\tau) = \sigma$ means executing machine $M$ on $\tau$ halts with output $\sigma$.

Now, inputs to these machines that halt on any arbitrary set of inputs have access more information than just the bits that make them up. Such a machine must somehow know when it has finished reading its input. Since our programs consist only of $0$’s and $1$’s, this information cannot come from a special end marker. Essentially, the machine is given the length of the input for free, even though this information is not encoded in the input string.

From an information-theoretic perspective, this is unsatisfactory. If we hope for inputs to convey only the information of their bits, our machines must know where the string ends. To circumvent this issue, we restrict our attention to prefix-free machines. A machine $M$ is prefix-free if whenever $M(\sigma)$ and $M(\tau)$ both halt with $\sigma \neq \tau$, then $\sigma$ is not a prefix of $\tau$ and vice versa.

But why just concern ourselves with $M$? Recall that universal machines can simulate every other machine, meaning for all machines $M$, and strings $\sigma$, there is some $\rho_M$ such that

\[U(\rho_M\sigma) = M(\sigma)\]where $\rho_M$ is the coding string for machine $M$ and $\lvert\rho_M\rvert$ is the coding constant for $U$, the cost of simulating $M$. Fortunately for us, universal prefix-free machines exist and we can define prefix-free Kolmogorov complexity to be $K(\sigma) = C_U(\sigma)$ where $U$ is prefix-free. In our formalization, we have the following

def Produces {α : Type} [Primcodable α]

(F : OracleFamily α) (σ : BinSeq) (n : Nat) : Prop :=

∃ p : BinSeq, p.length = n ∧ U F p [] = Part.some σ

def goodLengths {α : Type} [Primcodable α] (F : OracleFamily α) (σ : BinSeq) : Set Nat :=

{ n | Produces F σ n }

We define Produces as a proposition over strings $\sigma$ and natural numbers $n$ such that there exists some program with length $n$ and executing that program outputs $\sigma$. Then, goodLengths is the set of lengths that satisfies Produces for some $\sigma$. Finally, we can formalize Kolmogorov complexity, first relativized to a family of oracles, and second to no oracles.

noncomputable def plainKC {α : Type} [Primcodable α]

(F : OracleFamily α) (σ : BinSeq) : Nat :=

by

classical

let S : Set Nat := goodLengths F σ

exact if h : S.Nonempty then sInf S else σ.length

noncomputable def K (σ : BinSeq) : Nat :=

plainKC (asFamily empty) σ

While this may seem like theoretical nonsense, the very device you are reading this on is a universal machine (with some technical caveats we do not have to get into). Machines can be thought of as programming languages, and your computer or phone is a universal machine that compiles programs written in other languages.

Finally, we arrive at Kolmogorov’s definition of randomness: an infinite binary string is random if it is incompressible. Letting $A \upharpoonright n$ denote the first $n$ bits of the binary string $A$, Kolmogorov says a string $A$ is random if there is some constant $c$ such that for all $n$, $K(A \upharpoonright n) \ge n - c$.

A string $A$ is random if there is no program that can effectively compress any of its initial segments. The constant arises from the cost of simulating other machines, where different choices for universal machines yield different behaviour, but are all within a constant. Here, we find a representation of randomness that is defined by its ability to evade computation.

Measure Theoretic Randomness

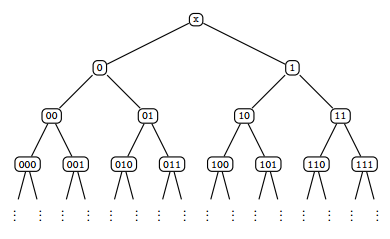

Per Martin-Löf took a different approach. He used measure theory to check how properties of strings can be encoded in its initial segments. These finite binary strings that we have been playing around with fortunately form a measurable space. Consider the tree below

If we think of the tree as having total measure $1$, then its subtrees with roots at (the binary strings) $0$ and $1$ each have measure $\frac{1}{2}$ since their sum gives the measure of the entire tree. In fact, as we go down the tree, we define the subtree with root $\sigma$ to have measure $2^{-\lvert\sigma\rvert}$. Let’s look at an example to see Martin-Löf’s intuition.

Consider $B$ to be the class of infinite binary strings such that the every odd bit is $1$. So $101010…, 111111, 1110101… \in B$ and $011111, 010101, 001010 \notin B$. Clearly, the strings in $B$ are not random, they follow some simple rule. Now, how can we use our tree to pin down where exactly these strings live? We will denote set of extensions of some finite string $\sigma$ as $\lbrack\mkern-2mu\lbrack \sigma \rbrack\mkern-2mu\rbrack$. It is now our goal to “capture” $B$ in a series of progressively more specific sections of the tree. For every $A \in B$, we have that $A \in \lbrack\mkern-2mu\lbrack 1 \rbrack\mkern-2mu\rbrack$. Only looking at $\lbrack\mkern-2mu\lbrack 1 \rbrack\mkern-2mu\rbrack$ is too restrictive since that set includes strings like $10000…$ which do not have $1$ at the third bit. In order to ensure that our third bit is $1$, it must be the case that $A \in \lbrack\mkern-2mu\lbrack 101 \rbrack\mkern-2mu\rbrack$ or $A \in \lbrack\mkern-2mu\lbrack 111 \rbrack\mkern-2mu\rbrack$.

Adopting Martin-Löf’s notation, we define a Martin-Löf test to be a sequence ${ U_n }_{n \in \mathbb{N}}$ of sets such that the measure of $U_n \le 2^{-n}$ and each $U_n$ is the union of such extensions. Taking unions of such extensions means that we are asking a question of the form, “Does there exist an extension of any of these finite strings which gives us our infinite binary string?” This is found using $\mu$-minimization, connecting us to our computable functions above. We can denote the measure of a set by $\mu(\cdot)$. For our example, $U_1 = \lbrack\mkern-2mu\lbrack 1 \rbrack\mkern-2mu\rbrack$ and $U_2 = \lbrack\mkern-2mu\lbrack 101 \rbrack\mkern-2mu\rbrack \cup \lbrack\mkern-2mu\lbrack 111 \rbrack\mkern-2mu\rbrack$. Notice that $\lbrack\mkern-2mu\lbrack 1 \rbrack\mkern-2mu\rbrack$ is half of our tree, so $\mu(U_1)=\frac{1}{2}=2^{-1}$ and $\lbrack\mkern-2mu\lbrack 101 \rbrack\mkern-2mu\rbrack \cup \lbrack\mkern-2mu\lbrack 111 \rbrack\mkern-2mu\rbrack$ is the union of two eighths of our tree, so $\mu(U_2)=\frac{1}{8} + \frac{1}{8} = \frac{1}{4} = 2^{-2}$. Try to see how you would define $U_n$ for each $n$ and verify that the measures behave nicely.

We call a class $C$ Martin-Löf null if there is a Martin-Löf test ${ U_n }_{n \in \mathbb{N}}$ such that $C \subseteq \bigcap_n U_n$. So our class $B$ is Martin-Löf null since the construction above gives such a Martin-Löf test. Martin-Löf nullity formally defines some reasonable property of our class in question. Finally, an infinite binary string $A$ is Martin-Löf random if ${A}$ is not Martin-Löf null. Viewing a Martin-Löf test as a query into whether some property holds of a sequence, $A$ is random if $A$ does not satisfy any property that is effectively describable.

Crazy enough, there does exist a universal Martin-Löf test. Meaning that this singular test encompasses all other Martin-Löf tests. While we can enumerate the test, it requires infinite questions which means we cannot decide in finite time whether something is random.

Gambling Randomness

Let’s shift gears. Say you have a single dollar and we sit down to flip a coin many, many times. You bet whatever money you have at each flip. Your final winnings will be based on how you choose to divide your current winnings at any given point between heads and tails. Any way you could possibly choose each of your bets we can model using some sort of a computable process.

We formally define a martingale to be a function $d$ from finite binary strings $\sigma$ to nonnegative real numbers that satisfies

\[d(\sigma) = \frac{d(\sigma0) + d(\sigma1)}{2}\]That’s right. The CT thesis in action! Effective functions producing the limits of human computation power.

This condition is known as the fairness condition and prohibits money from appearing out of nowhere, you can only make what you bet. Turning it to an inequality would yield supermartingales, similar functions with slightly different behavior. Alternatively, we can restrict $d$’s values to be approximable by a computable sequence of rational numbers from below which we call computably enumerable (c.e.) martingales. We say that a betting strategy succeeds on a sequence of coin flips if such a strategy results in infinite winnings. Formally, a martingale $d$ succeeds on an infinite binary sequence $A$ succeeds if

\[\limsup_n d(A \upharpoonright n) = \infty\]Finally, $A$ is random if no c.e. martingale succeeds on it. This notion of randomness says that an inherent trait of a random sequence is that no computable procedure can win infinite money betting on it.

They are all equivalent!

The notion of randomness as represented by incompressibility, measure theoretic tests, and c.e. martingales turn out to agree on everything! That is, each identifies exactly the same infinite binary sequences as random. Another instance, along with the CT thesis, of different formalizations of abstract notions converging to one: what began as very different formalizations of our intuitive idea of “lack of pattern” end up describing precisely the same phenomenon. When independent formalizations of the same intuitive concept consistently single out the same objects, that is evidence that we have stumbled upon something “real”, not just an artifact of the formalism.